Sport Spotlight: Wheelchair Rugby Edition

By: James SaWhat do you call a quadriplegic without his power chair?

One of the greatest misunderstandings in the realm of adaptive sports is the defining limits of quadriplegia. Quadriplegia is defined as having impairment in all four limbs and oversees a varied population that includes everyone from no motor function below the neck to the slightest of nerve damage in the hands. There are eight cervical vertebrae that determine upper body mobility which in turn can be used to explain the existence of varying levels of quadriplegia.

In an athletic context, this created a population of manual wheelchair users who were eager to be physically active and competitive but lacked the tools to be successful at wheelchair basketball (namely, hands that weren’t fleshy pancakes). Several brilliant Canadian quads got together on a basketball court and after some wheelchair collisions that occasionally involved a volleyball from time to time, created a grassroots movement that would eventually evolve into wheelchair rugby.

What is Wheelchair Rugby?

Wheelchair rugby is a sport designed specifically for quadriplegics. Athletes play four against four on a basketball court and dribble or pass a volleyball once every ten seconds. The objective is to score more goals than your opponent by crossing a goal line; any chair on chair contact along the way is not only allowed but actively encouraged!

Wheelchair rugby is a sport designed specifically for quadriplegics. Athletes play four against four on a basketball court and dribble or pass a volleyball once every ten seconds. The objective is to score more goals than your opponent by crossing a goal line; any chair on chair contact along the way is not only allowed but actively encouraged!

Although the game was designed to be inclusive, there are some quads who barely had more than a working set of biceps and some whose arms are so big they could have easily been mistaken for a professional linebacker from the waist up. In an effort to balance this while maintaining the inclusive nature of the sport, players are classed based on function (0.5 to 3.5), and out of a total starting line, those four players are capped at 8 points.

3.0 and 3.5 players are overwhelmingly dominant but they need “low point” players on the court in able to acknowledge the 8 point cap. This creates a balance of power, promotes inclusion, and creates a level of strategy that has earned the sport a nickname of “full contact chess”.

The State of the Sport Today

After having 40+ years to grow and develop, wheelchair rugby is developing into a refined and polished sport, especially on the international stage. A wealth of resources has been built up from game strategy to sport science and training methods. Spartan efforts of grinding and trial and error have been replaced with increasingly efficient and scientifically proven regimens. As a result, wheelchair rugby is in a golden age of a “bigger, faster, stronger” movement. The final cherry on top is wheelchair rugby has two unique trump cards that are catapulting its development at an exponential rate: better equipment and a function creep.

After having 40+ years to grow and develop, wheelchair rugby is developing into a refined and polished sport, especially on the international stage. A wealth of resources has been built up from game strategy to sport science and training methods. Spartan efforts of grinding and trial and error have been replaced with increasingly efficient and scientifically proven regimens. As a result, wheelchair rugby is in a golden age of a “bigger, faster, stronger” movement. The final cherry on top is wheelchair rugby has two unique trump cards that are catapulting its development at an exponential rate: better equipment and a function creep.

As manufacturers and athletes grow a better understanding of biomechanics, the rugby chair has evolved from a tough trash can on wheels to a sleek, powerful battering ram that truly compliments the ability of each individual user. Lower seat height, increased center of gravity, and cambered wheels have brought a level of speed and power that could never have been achieved in the days of playing in an everyday wheelchair and a pair of steel-toed boots.

Secondly, and perhaps the most hotly debated topic is the inclusion of non-spinal cord injuriy players who still fall under the umbrella term quadriplegia. This demographic includes quad amputees, neurological diseases, and other disabilities that haven’t quite found a home in other adaptive sports. Unlike traditional spinal cord injuries, many of these players don’t suffer from impaired blood pressure and intercostal lung function which gives them the ability to generate much more power. Coupled with increased trunk function, this created a noticeable influx in “high-point” players who immediately elevated the rigorous physical demands of the sport.

To focus on the positives about this level of inclusion:

Crafty, powerful all-around player Chuck Aoki (3.0) and blazing fast defensive star Kory Puderbaugh (3.0) may seem completely insurmountable, but their passion and athleticism is playing a huge part in improving the caliber of play across the board. Low point players are becoming drastically quicker and developing passing ranges previously thought unachievable. Chad Cohn, Lee Fredette, and Joe Jackson are all phenomenal 1.0 players who have the respect and attention of high point players everywhere. Mid-pointers are constantly smashing physical skill-ceilings, most notably Ernie Chun’s (2.0) tremendous speed and Joe Delegrave’s (2.0) ever-improving all-around game.

Note: All the mentioned players are CAF supported athletes who have made it to the Team USA Paralympic level. These athletes have been excellent stewards and role models for the spirit of adaptive sport: CAF is proud to support them in their endeavors.

Additionally, the advent of a higher level of speed and excitement has helped generate more media attention which aids in the development of sponsors as well as general awareness. Both factors are imperative to the future growth of the sport and the goal of transitioning from “coolest fringe sport” to mainstream spectator sport.

How do we grow Wheelchair Rugby?

Wheelchair rugby is not just about the players. The population also includes coaches, support staff, sponsors, fans, referees, classifiers, and therapists: the list goes on. Everyone’s contribution must be acknowledged and a conscientious effort made to elevate each other’s ability to succeed. Partnerships with major sponsors need to be honored and utilized to help maximize media impact as well as best serve the players. Referees, classifiers, and therapists are responsible for establishing the boundaries of the sport; there needs to be open dialogue on how to create a fair but competitive playing field. Players also have the responsibility to deliver a great spectator experience by competing to the best of their ability and demonstrating good sportsmanship. Finally, fans need to let their voice be heard and let mainstream culture and media know that able-bodied or adaptive, everyone is capable of achieving greatness and has a place in the community.

Wheelchair rugby is not just about the players. The population also includes coaches, support staff, sponsors, fans, referees, classifiers, and therapists: the list goes on. Everyone’s contribution must be acknowledged and a conscientious effort made to elevate each other’s ability to succeed. Partnerships with major sponsors need to be honored and utilized to help maximize media impact as well as best serve the players. Referees, classifiers, and therapists are responsible for establishing the boundaries of the sport; there needs to be open dialogue on how to create a fair but competitive playing field. Players also have the responsibility to deliver a great spectator experience by competing to the best of their ability and demonstrating good sportsmanship. Finally, fans need to let their voice be heard and let mainstream culture and media know that able-bodied or adaptive, everyone is capable of achieving greatness and has a place in the community.

Closing Remarks

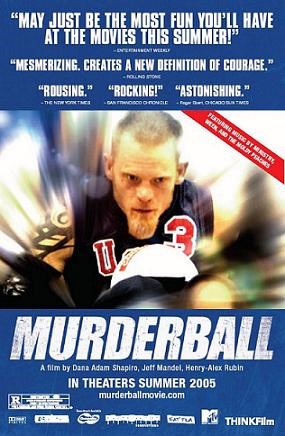

In 2005, a cult classic documentary called Murderball was released. It followed the lives of several USA players over the course of a couple years and showed not only their athletic careers but their dynamic and fulfilling personal lives. Purely anecdotally, I’m willing to bet at least 90% of the quads who were injured after its release were introduced to the film, and subsequently, the great sport of wheelchair rugby. Lying in a hospital bed and doing rehab, seeing someone just like me who was happy, healthy, independent, and competitive wasn’t just a light at the end of the tunnel, it was a spark that completely blew the darkness out of my mind and gave me a new lease on life.

In 2005, a cult classic documentary called Murderball was released. It followed the lives of several USA players over the course of a couple years and showed not only their athletic careers but their dynamic and fulfilling personal lives. Purely anecdotally, I’m willing to bet at least 90% of the quads who were injured after its release were introduced to the film, and subsequently, the great sport of wheelchair rugby. Lying in a hospital bed and doing rehab, seeing someone just like me who was happy, healthy, independent, and competitive wasn’t just a light at the end of the tunnel, it was a spark that completely blew the darkness out of my mind and gave me a new lease on life.

Therein lies the greatest part of the greatest sport nobody has ever heard of. Wheelchair rugby has a place for the newest player fresh out of the hospital post-injury to the most celebrated of Paralympians. Under one roof in the sport so many of us called home, we are given a community that helps people of all abilities grow, develop, and enrich their own lives as well as those of others. Hopefully with the joint effort of our entire community, we can help bring attention to the ability and inclusion of adaptive athletes by smashing stereotypes, one hit at a time.

_____________________________________________________

WATCH a quick clip to get a feel for the game.

Help support the next generation of wheelchair rugby players. DONATE NOW to CAF and your funds will help buy much-needed adaptive sports equipment that is often prohibitively expensive.

If you’re physically challenged, see if you’re eligible for a CAF grant and APPLY NOW.

To stay informed about CAF news and adaptive sports updates, SIGN UP for our newsletter.